A few things to bear in mind about South Korea (for more information, please visit the website of the Adoptee Solidarity Korea Association:

Intercountry adoption from Korea is the involuntary removal of a person from his or her culture, language, and rights to his/her personal history. The significant cultural differences between the birth country and the adoptive country render it extremely difficult for an adoptee to reclaim his/her past history and early life experiences let alone access Korean language and culture.

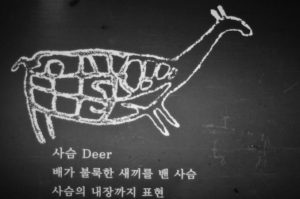

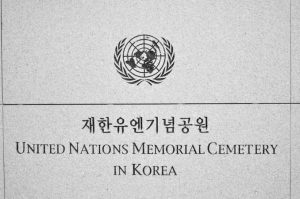

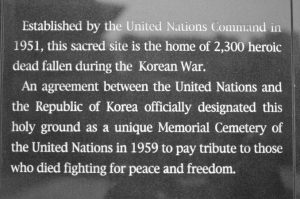

As the Republic of Korea has entered into the 21st century, among the numerous issues remaining unresolved is the issue of intercountry adoption. Intercountry adoption, a remnant from the Korean War, began as a humanitarian effort instigated by American Christian missionaries; however, by the 1980s intercountry adoption had become a government-regulated de facto industry of child exportation with over 66,000 children adopted abroad in that decade alone. Today, Korea is the only industrialized nation that systematically sends its citizens abroad for adoption. According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, 155,044 Korean children have been adopted to 15 different Western countries between 1953-2004; these countries include the United States (103,095), France (11,090), Sweden (8,953), Denmark (8,571), Norway (6,080), the Netherlands (4,099), Belgium (3,697), Australia (3,147), Germany (2,352), Canada (1,841), Switzerland (1,111), New Zealand (559), Luxembourg (492), Italy (382), and England (72).

The on-going practice of sending Korean children to Western countries to be raised by non-Korean parents continues to mar Korea’s image perpetuating the assumptions that Korea is still a poor, developing country unable to take care of its so-called “orphans”. In truth, the absolute majority of the children sent abroad for adoption, are indeed not orphans at all. The over 2,000 children per year that are surrendered for overseas adoption are born to single, unwed mothers in their late teens to mid-20s.

Obviously such a phenomenon is not a reflection of Korea’s current economic status nor is it reconcilable with the reality that Korea’s birthrate is at an all-time low. What the continuing practice of intercountry adoption does reflect is the lack of social services, rights for women and children, and the government’s continued dependence on intercountry adoption in lieu of developing a mature social welfare system to deal with the needs of its citizens. In addition, Korea is not in compliance with either the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child or The Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption – both of which stipulate that when all other possibilities have been exhausted, intercountry adoption should be the final option

Intercountry adoption is a human rights issue, with the rights of Korean children who are adopted abroad put into question, not to mention the routine violations of birth mothers’ rights to decide – in an informed, non-coercive manner – the future of their own children. It is time that Korea takes the moral and financial responsibility for the well-being of its own children and the mothers who give birth to them. It is time for the end of intercountry adoption.

According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare (2001-2005), 99.7% of intercountry adoptions were the children of single mothers, not orphans. If a single parent decides to raise his or her child alone, there is only minimal, short-term assistance offered by the government

To summarize: Korea has the financial ability and moral responsibility to care for the upbringing of its own children rather than sending them abroad for adoption. According to international standards, children’s rights are violated when they are forcibly removed from their country of origin and mother’s rights are violated when they are coerced into surrendering their children. As Korea continues to develop its social welfare system, international adoption should no longer be a viable option.